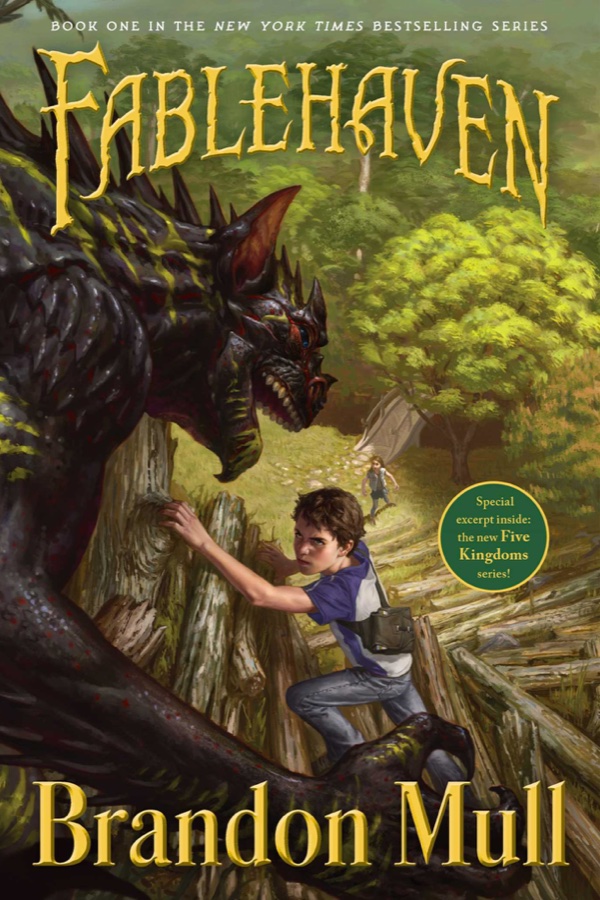

Brandon Mull’s Fablehaven is an absorbing, well-plotted, and enchanting series that offers young readers real goods, but sometimes wanders too close to real darkness. Mull goes out of his way to showcase virtue, providing discussion questions so readers don’t miss the lessons. He even portrays the sexes as really distinct, but complementary, an extremely defiant feature in a contemporary mainstream series. However, there’s an unsettling dualism in his imaginary world that partially offsets its best qualities, graying the light that would otherwise shine brightly from the author’s thoughtful pen.

Kendra and Seth Sorenson’s magical adventures begin, naturally, when mom and dad are out from underfoot. In a cozy attic, on their grandparents’ strange estate — a large piece of wilderness crying out to be explored — closely guarded magical secrets await discovery. Mull does an excellent job of showing Seth and Kendra’s process of discovery, and he awakened my own sense of childhood delight in possibilities and mysteries that lie just beyond the edge of sight. In Mull’s well-built fairy world, the greatest wonders are always there, if only you have eyes to see. Is that woodpile really just a woodpile? Are you sure that’s a beetle scurrying across the porch? The books are also full of substantive reflections on anthropological, moral, and metaphysical truths too numerous to fully detail, and there are many little details that stand out for their ordinary decency.

The Sorenson family feels normal and healthy. Grandpa and Grandma Sorenson clearly love each other, though they verbally spar on occasion. Kendra and her younger brother Seth are well-drawn girl and boy characters. Kendra is sweet, feminine, pure of heart, and sensible, with a maturity that keeps her on the straight and narrow, and a heart that wants to fall in love. Yet that same sensibility and sweetness blinds her, on occasion, to hard realities. Seth is all boy, a scrappy, tree-climbing, trouble-making handful, who always keeps his hand-assembled “emergency kit” close by. His antics are sometimes hilarious, but at other times could literally be the death of everyone. Just when you’re ready to shake Seth for his incredible stupidity and foolhardiness, he surprises you by doing something truly courageous and necessary. Though the children’s parents are “unbelievers” (in fairies, that is), one brief scene shows that they care about what movies their children are watching, and about the company they keep.

Courage, prudence, justice, and purity of heart seem to be the virtues or qualities the author most highly prizes. The book is full of dialogues — some of them a little too long and wordy — about whether a particular course of action is really courageous, or just foolhardy. Characters agonize about finding the most prudent course of action, when no option seems safe or ideal. Hard justice is meted out to wicked beings that cannot be trusted, and, as the thickening plot reveals, a basic question of justice lies at the heart of the conflict between the allies of good, and those of evil. Kendra’s surpassing purity of heart, the fact that she is—as the novel explicitly states—a virtuous maiden, is precisely the quality that makes her such a conduit of light. And as one character puts it, if Seth’s courage doesn’t get him killed, it could someday save the world.

The novels show a pervasive interest in questions about the nature of being. For example, a major plot point revolves around the assertion that “anything that has a beginning has an end.” The second book goes into detail about the difference between intellect and emotion, and how the latter can distort (or sometimes amplify) the former. Beings who are oriented toward darkness cannot really be trusted. Fairies are beings of light, and so in some way oriented by their nature toward good, but at the same time are not, as one character notes, “good as you think of the word good,” because (with a few exceptions) they don’t truly choose the good, a distinction the author comes back to several times. They are creatures of light, but humorously vain and sometimes petty. Indeed, Mull’s fairy world quite deliberately, though superficially, resembles the world of nature, in which some creatures — butterflies and cows, for example — seem light (i.e. good), while others — reptiles and spiders and such — seem dark. This would be fine and useful, if the author could leave well enough alone, but he cannot. Mull is not only an exceptionally talented plotter, he is also logical to a fault.

Fairies have always occupied an ontologically ambiguous place in European stories. Gawain’s Green Knight, for example, doesn’t quite fit the profile of an angel or a devil. Fairies in general are too capricious to be purely good, too useful and wonderful to be bad. In their dangerous mystery, they embody and personify man’s precarious relationship with a fallen world, and with degrees of nobility and profanity in nature’s hierarchy. To that extent, it makes sense for creatures to be oriented in degrees toward “light” or “darkness,” with these categories ambiguously distinct from but related to good and evil. Mull puts this distinction to several good, or at least fun uses. But he also takes up these questions in such direct fashion that he is forced to have characters say things like, “I’ll agree that creatures of light can be deadly — consider the naiads, who drown the innocent for sport … And creatures of darkness can be helpful — look at Graulas [a demon], supplying key information, or the goblins who reliably patrol our dungeon.” Mull treads this ground again and again, especially in Seth’s storyline. At times he goes too far in the direction of saying that evil is necessary/useful, or he creates moral situations that are so complex that they are likely to confuse some young readers. Seth’s story arc is the primary example of this, and unfortunately it is not possible to discuss without a major spoiler. For a spoiler free review, please skip the next two paragraphs enclosed within line breaks.

At the end of the second book, Seth disobeys his grandparents — attempting a dangerous and necessary course of action — and takes on an evil entity, defeating it against all hope. In the next book, it’s revealed that by coming into contact with this evil, Seth was somehow marked, becoming a shadow charmer, a person who can command and even counsel dark entities such as trolls, zombies, wraiths, and even demons. In yet another risky endeavor, Seth confronts and consults a demon named Graulas. In Fablehaven, demons are not devils, but long-lived beings of pure wickedness who nevertheless fear a terrible afterlife toward which they are apparently destined. Near death’s door, Graulas confesses his admiration for Seth’s bravery in facing a dark creature called a Revenant. He empowers Seth, confirming the dark gift the boy had inadvertently received in the course of performing a virtuous action. The author makes a point of showing that Seth didn’t explicitly agree to the nascent gift, or to Graulas’s confirmation, yet Seth immediately makes use of the gift to perform a dangerous feat that is arguably necessary for the ultimate triumph of good. Seth can only accomplish this deed because his shadow charming makes him immune to the feeling of guilt, which feeling is normally amplified by a particular spell.

When he is victorious, and for the equivalent of about two books, this entire scenario is portrayed as an example of how taking risks, such as “confronting” demons can sometimes be the right choice. It is further suggested that being an “ally of the night” and “counselor of demons” doesn’t necessarily make a person evil, provided that the person only makes good choices. Seth is therefore a rare, but necessary thing: a virtuous shadow charmer. Nevermind that this flies in the face of one of the books other important and explicitly stated lessons: that we cannot do evil that good may come of it. Thankfully, it all turns out to be an elaborate trick by Graulas, one which almost destroys the world. However, one has to read the series all the way to the end to discover this, as even major characters on the side of good seem to reinforce the impression that Seth’s dangerous consultation with a demon was necessary. Furthermore, the book never really shakes the idea that darkness and dark powers have an appropriate place, as on several occasions, Seth’s “darkness” and Kendra’s light, when combined, result in unique powers. Even more troubling, there is a scene near the end of the last novel where Seth, in order to take possession of a weapon — which itself combines the powers of light and darkness — must confront another evil entity; the confrontation ends in Seth taking the undead entity’s life at that entity’s own request. Is this magical euthanasia, or would it be a justified killing? It’s very hard to say, even for an adult.

The difficulty of light/dark dualism is that it makes evil necessary. The Manichaean error, which seems to pop up all over the place nowadays in children’s literature and television, involves a basic confusion about good and evil: it puts them on an equal but opposite footing. It sees light and darkness as necessary corollaries. But darkness isn’t something. It is the absence of something, namely light. However, if mistaken for a kind of being, darkness/evil will inevitably be seen as necessary. Rather than being an absence, or a privation, it becomes “the opposite of light.” This kind of thinking leads to a kind of Hegelian process theology in which light and darkness act as a thesis and its antitheseis, working toward some ultimate synthesis — Balance. The balance then becomes the “Enlightened” end, and the good is left behind by a new state of affairs that is beyond good and evil. For this reason, it is concerning that when Seth and Kendra join hands, they can parley with dragons, who are such sophisticated creatures that they otherwise regard humans as we would regard mice. On the other hand, most of Mull’s dragons are evil, as are all of his witches, and all of his demons, and the author certainly advocates for the cause of goodness over evil. Still, the distinction between being fallen and being dark by nature is extremely important.

It’s one thing for a character that is good by nature to fall, and thereby become something evil “by nature.” There are examples of such in Fablehaven, but they are specifically distinguished from beings that are naturally dark/evil. But a naturally evil being would entail a total disconnect between morality and being. In such a world, no one could say an action was right, only that it was right for him. Meanwhile, evil beings would only be acting toward the good of their nature — which is to be evil. This concept is nonsense. It can be fun nonsense if not examined too closely; after all, it at least superficially parallels the truth that many things in creation are dangerous if not used correctly, or with proper limits. It parallels the truth that danger and risk are part of life, and that there’s a kind of hierarchy of nobility in nature. It also parallels the truth that the masculine element in the universe, as embodied by the lovable punk Seth, is oriented toward contending with the harder lines of reality. There’s a wonderful scene in the third book that especially illustrates this series’ weird tension between the refreshingly true and good, and the darkly problematic. As an evil being chases the children, Kendra commands a magical ally to stop the creature without hurting him. Seth, seeing the situation much more clearly calls out the command, “Break his legs, but don’t kill him!” Seth is willing to do the “dark” but necessary thing, whereas his sweet sister can’t see that violence is sometimes necessary. Yet the author somehow fails to see clearly that if an action is necessary then it is also good, and therefore “light,” not dark. All this muddiness undermines an otherwise highly recommendable series.

Meanwhile, the writing ranges from surprisingly good, to a little choppy. The first novel was particularly well written and even touching. There were moments when I was genuinely charmed, frightened, amused, or even moved, and the books as a whole were extremely hard to put down. As previously mentioned, Mull is a superb plotter, and really understands the art of the slowly developing you-should-have-seen-this-coming shocker. The series is filled with intrigue, and the villain is the best I’ve seen in years. I stand amazed at how well Mull prefigured all five books in the nucleus of the first, and yet the first book remains great reading on its own. While it’s true that the last three books feel a bit too video-gamey, with characters solving puzzles and defeating bosses to collect whatever MacGuffin they’re after, these books are far superior in every way to both the Artemis Fowl , and Percy Jackson series. Aside from the philosophical problems raised above, my only real gripe was the ending, which was unsatisfactory, and had several loose ends. Still, Brandon Mull’s Fablehaven delighted me, despite its flaws. I truly wish I could give it a wholehearted recommendation. To parents and children who regularly discuss and argue back with the books they read, I give a qualified recommendation, just short of enthusiastic. Parents that prefer novels with a totally straightforward and unproblematic account of good and evil may want their children to pass by the marvelous, but morally complicated world of Fablehaven.

Discussion Questions

- In the afterword to the last book, Brandon Mull states his desire to write family-friendly books. In what ways was Fablehaven family friendly?

- Were you satisfied with the ultimate direction of Seth’s storyline? Did Fablehaven’s ending “click” for you? Why or why not?

- Often contemporary female characters are shown using martial arts or otherwise being strong enough to beat up large male bad guys, but Kendra is rarely shown in battle. Which actions made her seem stronger as a character, her actions that saved the day at the end of the first Fablehaven book, or her action that helped saved the day at the end of Keys to the Demon Prison?

- When discussing Kendra’s and Seth’s parents’ unbelief, a character notes that unbelief is a choice. Have you ever considered the difference between simply lacking a belief in something, and unbelief?

- The villain is shown doing evil in order to achieve what he believes is a greater good. What’s wrong with this?

- Throughout the series, good characters occasionally tell lies of convenience, especially when dealing with hostile forces. Is that right? Do we have a general obligation to tell the truth, or only to tell the truth when we perceive the questioner to be on our side?